Practical Guide to Renewable Project Finance Modeling Fundamentals

Practical Guide to Renewable Project Finance Modeling Fundamentals

Introduction to Practical Guide to Renewable Project Finance Modeling Fundamentals

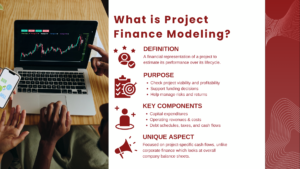

Project financing is one of the most important fields in energy investment due to the fact that in the recent development due to the rapid increase in renewable energy projects worldwide, the project finance modeling comes into consideration. Project finance, in contrast to corporate finance, investigates the question of how much money will be needed to finance a single asset or several assets. This is of particular importance to renewable energy, where the capital investment necessary in a solar farm, wind park, or biomass plant is large at the outset, but produces steady long-term cash flow.

The modeling of project finance enables the developer, investors, and lenders to assess the risk-Font combination of the renewable project. It is both a planning and decision-making instrument and it directs where capital is used and what prices will be charged and how much risk must be taken. The strong model is not just about revenues to be collected and expenses to be incurred, but the combination of engineering assumptions, financing terms and risk scenarios into a single framework that can be leveraged to achieve contract and financing terms in a confident manner.

The modus operandi and basis of renewable project finance modelling are also considered beforehand necessities of anyone wishing to participate in the renewable investment sphere, whether as an analyst, consultant, developer or financier.

Fundamentals of Project Finance in Renewables

Renewed project finance entails essentially the same as giving a project future cash flows to support finance. Project finance in renewable sources are not based on the balance sheet of the sponsor as is the case with corporate loans but on the capacity of the project to earn its own revenues often through contracts such as the long term Power Purchase Agreements (PPA).

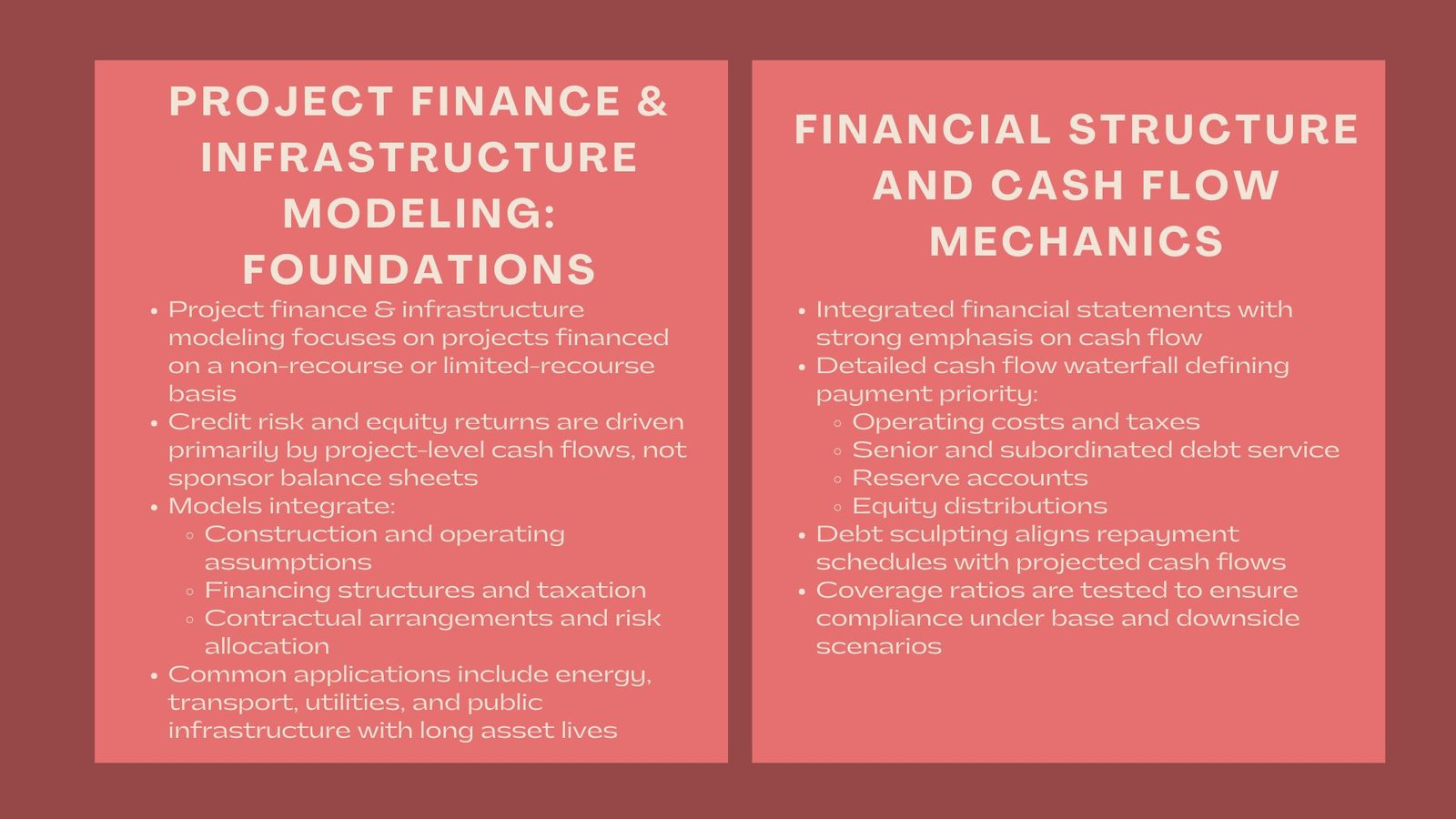

Non-Recourse or Limited Recourse Financing

A major feature of project finance is that lenders do not (or have little) access to the balance sheet of the sponsor. Rather, it is performance-based, in terms of repayment. This structure is particularly appealing in renewables where projects tend to be developed by special purpose organisations or consortiums of investors, who want to keep project specific risks within a project.

Risk Allocation

The other basic principle is that risk should be distributed amongst stakeholders. In general, the risks for renewable projects are construction delays, cost overruns, technology performance, resources and regulatory change. Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) agreements, Operations and Maintenance (O&M) contracts, PPAs and others share these risks between developers and contractors, operators and off-takers.

Revenue Predictability

Relatively predictable revenue is one of the advantages renewable energy projects have over other infrastructure investments. As an example, 15 to 25-year PPAs on solar generation will enable solar companies to assume fixed electricity prices over the term of the PPA generating stable incomes. These revenue assumptions however require generation to be forecasted correctly either on the basis of solar irradiation or wind patterns.

These fundamentals form the backbone of project finance and directly shape how models are built and evaluated.

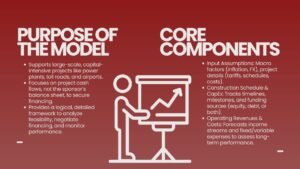

Key Components of Renewable Project Finance Models

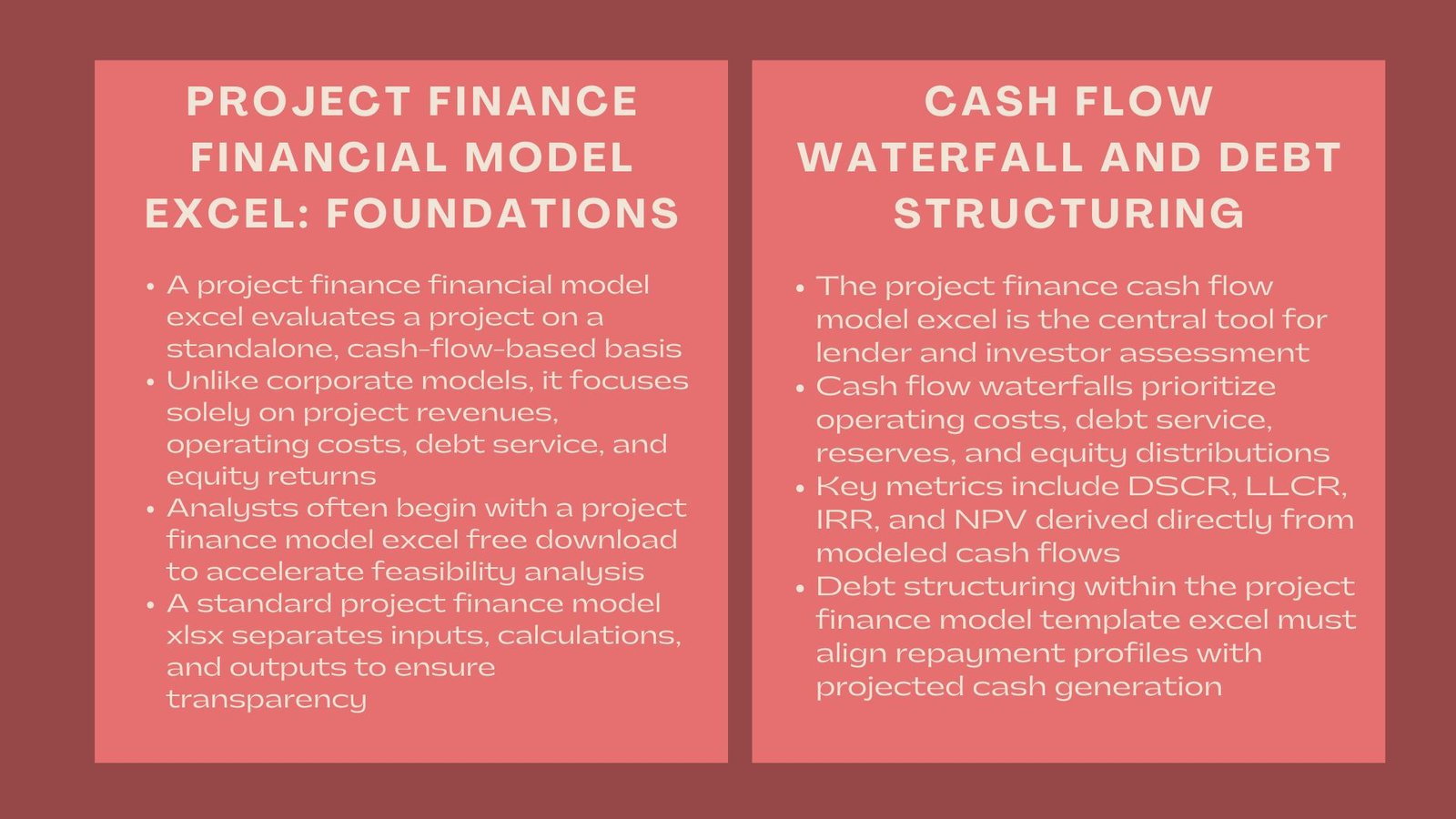

Financial modeling of renewables should be systematic and convert technical/commercial data/information, to financial figures. All the elements of the model should blend into one another to allow precision and validity.

Assumptions and Inputs

All the models start with a collection of inputs. In case of the renewable sources, such specifications involve power plant generation capacity, degradation rates, capacity factors, and construction schedules. Assumptions involving finance, such as terms of debt, equity contributions, tax rates and inflation are equally significant. The quality of a model in use frequently relies on the validity of its assumptions, which should not only be realistic, but also adequate data sources are required.

Construction Phase and Capital Expenditures

The initial cost of construction is usually heavy. This becomes an elaborate construction schedule, capital expenditure (CAPEX) analysis and draw-downs of funds in the model. Timing assumptions are especially sensitive, since they can cause interest charges in the construction period and move the date on which the project is operational.

Operating Revenues and Costs

Revenues of this project rely on the quantity of electricity generation and pricing processes as soon as the project is launched. The expenses are on the operations and maintenance, insurance premiums, renting land and occasional repair. Renewable models should also consider degradation in generation capacity with time in that solar panels or wind turbines generate less power annually.

Debt Service and Financing Structure

Project finance schemes include a matrix of repayment of the loan which in many cases is a sculpted payment basis on the cash flows of the venture. This guarantees that debt is serviced utilising cash where it is available without jeopardising target debt service coverage ratios (DSCRs). However, equity investors require returns that are expressed in terms of internal rate of return (IRR) and net present value (NPV) and, therefore, the distribution must be correctly modeled.

Sensitivity and Scenario Analysis

Since renewable projects are faced with various uncertainties including weather patterns or policy changes, sensitivities should be tested on the models. By way of example, decreasing the generation of energy by a 5 percent output or changing the interest rates may provide an indication of the robustness of the project to unfavorable situations. With scenarios, the stakeholders can also negotiate with terms and derive the information of which risks are highly important to be managed.

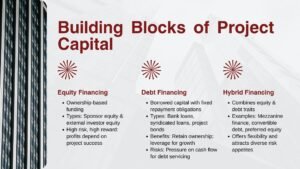

Structuring Finance for Renewable Projects

Modeling issues become intertwined with the financing decisions in the financial structure of renewable projects. Structuring is the balancing of debt with equity, choice of instruments used to fund the project, and setting repayment terms to coincide with the flow of cash contemplated in the project.

Debt vs. Equity Mix

A large part of the renewable projects is funded through debt financing due to the predictable and steady nature of cash flows. Financial institutions (lenders), on the other hand, must have assurances that the project is capable of realizing its commitments. Equity investors take greater risk in an effort to receive residual profit left after the debt payment. The precise debt/equity ratio varies by the risks of the project, local laws, and interest rates of lenders.

Role of Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs)

The backbone of revenue certainty is PPAs. They ensure that a purchaser of the electricity of the project is guaranteed at predetermined terms of prices which may be indexed to inflation. A robust PPA with a reputable off-taker to the financiers, creates less risk of revenue and enhances the bankability of the project. When the merchant projects sell energy on the market, modeling is further complicated, because the cash flow estimation must include the volatility of the prices.

Tax Equity and Incentives

Tax credits, subsidies, or feed-in tariffs are available in certain jurisdictions to renewable projects. By way of example, the U.S. exploits the tax equity structure to finance investment tax credit (ITC) or production tax credit (PTC). The latter should be taken into consideration in models as they have the potential to enhance the economics of the project, as well as distort patterns of financing.

Refinancing and Exit Strategies

Refinancing of many renewable projects occurs at some point during the post construction stage after the operational risks have been reduced. A strong model enables the sponsors to predict the possible advantages of refinancing, including the reduction in the cost of interest or leverage. The model also inculcates exit strategies of equity investors like the sale of the project to other institutional investors to determine the long term returns.

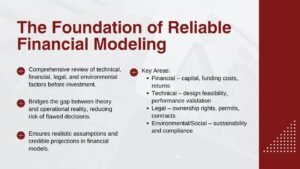

Practical Challenges in Renewable Project Finance Modeling

Although the method is well structured, modeling of the renewable projects can be a challenging affair that must be navigated well.

Data Quality and Resource Assessment

Credible or verifiable data on wind speeds, solar irradiation, or supply of biomass is very important and may be complicated to get and verify. Resource estimation fails to consider the actual extent to which the project will be financially viable since misjudgments may be made in exaggerating.

Technology and Performance Risks

The risks are there even though renewable technologies have matured. As an illustration, faults that may cause undesirable deterioration in the solar panels or idleness in the wind turbines may interfere with generation. Consideration of these risks is needed and this should be mandated under model assumptions so as not to overestimate the revenues.

Policy and Regulatory Uncertainty

Government policies like subsidies / tariffs can make renewable energy projects sensitive to them. The change in the economy of the projects due to sudden policy change may have a dramatic effect and scenario planning using models would prove essential.

Complexity of Contracts

The interdependent nature of EPC, O&M, and PPA contracts give rise to the presence of a web of dependencies that has to be accommodated in the model. Contract terms mismatch also tends to have a disastrous financial implication in the event of incompatible construction deadlines and PPA start dates, among others.

It is only by acknowledging such difficulties that developers and financiers will be able to design a model not just technically sound but also realistic in terms of projecting the uncertainties of the real world.

The Role of Project Finance Models in Decision-Making

Finally, project finance models are conversational tools, and not ideal forecasters of the future. They are useful as they bring forth transparency, risk quantification and a convergence of interests of parties. The models evaluate the loan-worthiness of projects and debt service ability to the lenders. In the case of equity investors, they indicate the possible returns and they exhibit exit opportunities. Developers use them as a form of planning tool and are always certain that the contracts, financing and operational strategies are related to the economics of the project.

An organised renewable project finance framework does not just make funding easier but will also instill confidence in the people as the renewable energy industry scales upwards to help achieve the global sustainability objectives.

Conclusion: Building the Foundation for Sustainable Growth

Renewable project finance modeling is an interdisciplinary field with some overlap between finance, engineering and policy. It integrates the technical assumptions and the financial structures so as to offer an entire scheme on which the viability of the renewable investments can be evaluated. The generic aspects, including non-recourse financing, risk transfer, and revenues clarity, determine the structure of models, and CAPEX, OPEX, debt service, and sensitivities are the features of the key aspects that lead to accuracy and robustness.

With the current interest in renewable energy growing as a focus of global investment, the finance models that can be used to structure, negotiate and execute projects are only set to gain significance. Creating a sustainable energy future means that the impact of professionals that master these fundamentals will not only promote successful projects but they will be part of advancing the sustainable energy future.